By EFREM TESFAGABR

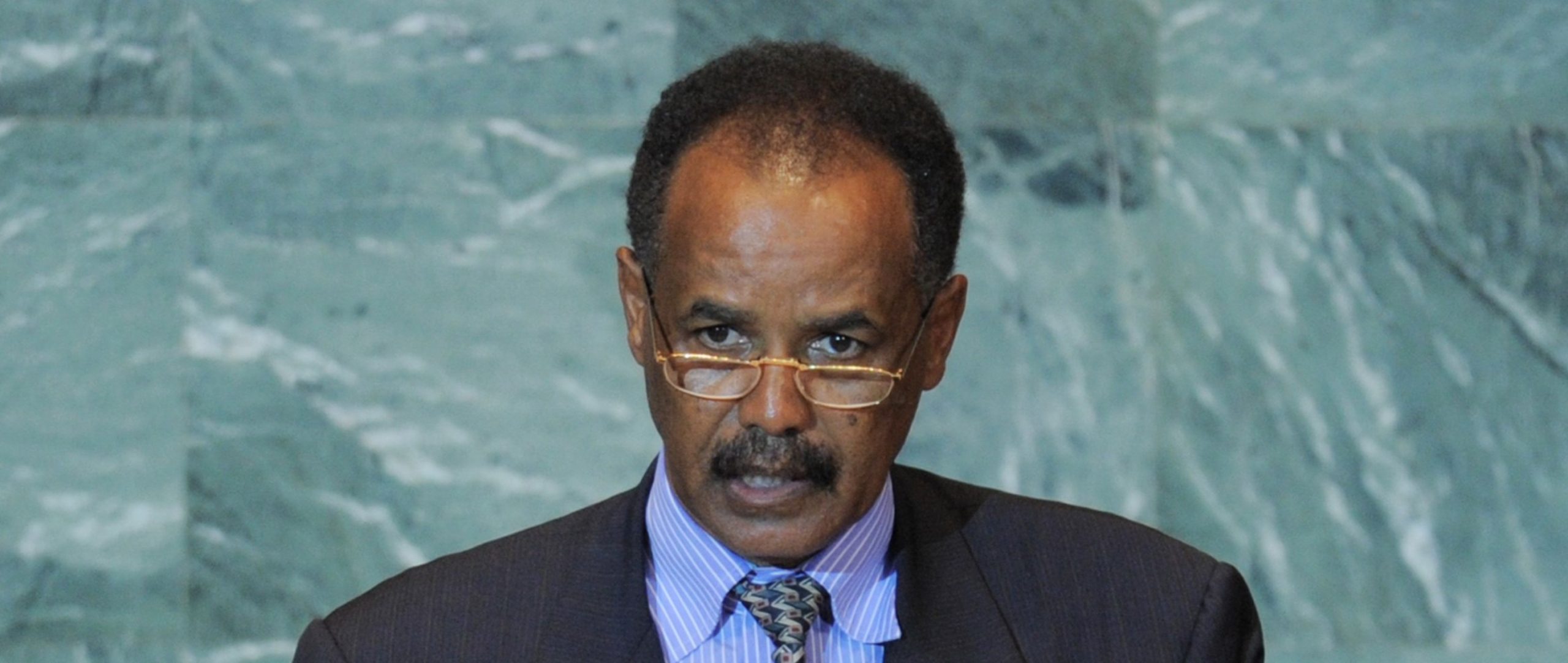

Eritrea, a small nation on the Horn of Africa, is once again at the center of grave international concern as new evidence emerges of gross and systematic human rights violations.

Despite long-standing global scrutiny, recent reports have intensified focus on Eritrea’s involvement in war crimes, its brutal internal policies, and its efforts to evade international accountability.

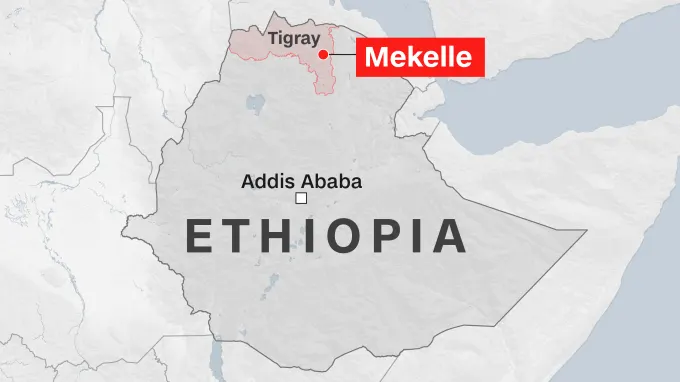

Wartime Atrocities in Tigray: A Legacy of Trauma

Eritrean Defense Forces (EDF), operating alongside Ethiopian troops during the Tigray War (2020–2022), have been accused of committing some of the most egregious atrocities seen in modern conflicts.

According to a detailed investigation by The Guardian in June 2025, Eritrean soldiers were responsible for widespread sexual violence against Tigrayan women, with survivors describing unimaginable brutality: gang rape, sexual torture using foreign objects, and permanent bodily harm.

In several cases, doctors reported finding rusted screws, nails, and pieces of metal forcibly inserted into women’s reproductive organs — a pattern suggestive not just of rape, but of deliberate acts of mutilation and sterilization.

Even after a ceasefire was declared in 2022, eyewitnesses and survivors claim that EDF forces remained in the region, continuing a campaign of violence, looting, and extrajudicial killings.

A report from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights corroborated ongoing abuses and emphasized the complete lack of accountability.

Torture, Disappearances, and the Reign of Fear

While international focus often centers on Eritrea’s role abroad, the government’s domestic repression remains severe.

Testimonies from former detainees, published by The Guardian earlier this year, revealed systematic torture in Eritrean prisons.

Detainees described being held in underground cells, shipping containers, and metal cages — often without trial, charges, or even formal arrest.

Torture methods included being suspended by the arms for hours, severe beatings, and confinement in stress positions.

Many prisoners were disappeared for years, with families never notified of their whereabouts.

Some, like political prisoners from the reformist G-15 group or religious minorities, have been held incommunicado for over two decades.

Indefinite National Service: A Life Sentence

One of Eritrea’s most criticized policies is its system of compulsory national service. Though officially limited to 18 months, in practice, conscription is indefinite. Thousands of young Eritreans — both men and women — are forced into military or forced labor under harsh conditions, often lasting for decades.

Many are subjected to physical and psychological abuse, including sexual violence against female conscripts.

Those who try to flee face imprisonment or worse. Families of draft evaders are punished with fines, loss of property, or eviction.

Border guards have been known to operate under a “shoot-to-kill” policy for escapees — a reality that has turned Eritrea into one of the world’s top refugee-producing countries per capita.

Religious Persecution and Media Silence

Eritrea permits only four recognized religious groups; all others are banned, and their followers frequently face persecution. As of early 2025, more than 100 Christians — including women and children — remained detained without trial, some for attending unregistered church services.

Jehovah’s Witnesses, in particular, have long been targeted for refusing military service and allegiance to the state.

Independent journalism is virtually non-existent.

All privately owned media was shut down in 2001, and journalists remain imprisoned to this day. Among them is Dawit Isaak, a Swedish-Eritrean journalist who has been held without charge or trial for over 20 years — making him one of the world’s longest-detained journalists.

Dodging Accountability at the United Nations

In June 2025, Eritrea submitted a motion to terminate the mandate of the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Eritrea.

The mandate, active since 2012, has played a critical role in documenting abuses and advocating for victims. Eritrea’s effort — supported by Ethiopia, Russia, and Sudan — signals a clear attempt to sidestep international oversight.

If successful, this move could dismantle one of the last remaining mechanisms for holding Eritrea accountable on the world stage. Human rights organizations and several Western governments have condemned the attempt, warning that it would embolden the regime and silence survivors.

Conclusion: A Call for Renewed Global Action

Eritrea’s human rights crisis is not new — but the scale and brazenness of recent violations demand renewed attention. The nation’s involvement in war crimes, use of sexual violence as a weapon, systemic torture, and repression of basic freedoms presents an urgent moral and legal challenge.

As Eritrea tries to deflect international scrutiny, the voices of survivors must be amplified.

The global community — including the UN, African Union, and international courts — must reaffirm its commitment to justice, accountability, and the dignity of the Eritrean people. Silence is complicity.