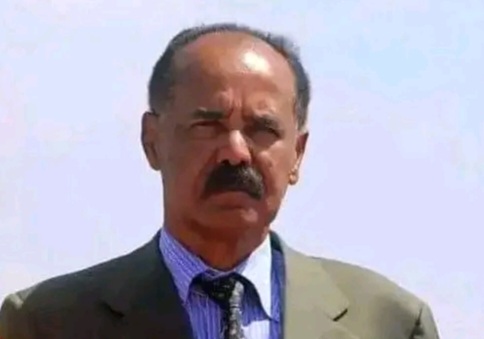

As it may be recalled, local media had conducted an extensive, four-part, interview with President Isaias Afewerki on domestic and international issues during the months of February and March 2023. The current interview deals with, and is focused on, the dyanmics, ramifications and future trajectory of the conflict in the Sudan.

Question: The Al-Bashir regime had posed a considerable security threat to the region at large, and neighboring countries, including Eritrea, in particular, on account of its fundametalist religious agena. Its subsequent ouster from power in 2019 due to the wrath of the Sudanese people gave rise to an atmosphere of hope and optimism in the Sudan as well as the region. The new reality ushered in a restoration and enhancment of bilateral ties between Eritrea and Sudan that was reflected in continous diplomatic shuttles and consultations. Taking into consideration the legacy of the Al-Bashir regime, what are the causes and defining features of the unnecessary conflict that has engulfed the Sudan at the present time

In view of Sudan’s geostrategic importance in the Horn of Africa, the Red Se and beyond, the developments that have unfolded in the Sudan cannot be underestimated or taken lightly. The post-2019 era is characterized by specific dynamics that raise questions about its genesis and development. But, it must also be examined within its historical context; from whence it came and how it unfolded.

The principal challenge for all peoples, whether in the Sudan or in any other underdeveloped country, is nation-building with its different dimensions; specifically, its socio-economic, cultural, and security aspects. Any discussion of the current situation must accordingly begin with examining its origins. If the aim is indeed to bring a lasting solution, stability, peace, growth, and development, then the root challenges must first be solved.

The period from Sudan’s independence in 1956 until 2019 can be roughly divided into three stages; the Al-Azhari period (1956-1969); the Nimeiri years (1969-1989); and the National Congress Party or Islamic Revolution (1989-2019) regime. Relative to other African countries, the Sudan occupied a more developed status – by all measures – during the first two stages. The nation-building process was quite advanced in these phases. This was especially true in the first 20 years of the Numeri period in which the process gained acceleration and was moving in a positive directon. This does not mean it was completely free of challenges. There were the problems of the South and other regions. Nevertheless, the process was progressing well in spite of these challenges.

In 1989, however, Political Islam, which technically began in 1983 during the last years of Numeri’s rule, took center stage. This Islamic movement, spearheaded by the Muslim Brotherhood (al-aKhwan al-Muslimin), was a continuation of what was founded in 1928 by Hassan al-Banna. But throughout the decades, it falied to make any discerbible influence within the ranks of the Sudanese people. Political movements based on this philosophy did not have any influence that exceeded 4 or 5 percent of the population. In 1983, however, owing to the general conditions of the Cold War, this movement begun to readjust its position, alongside various other parties.

I will not delve into all the myriad details. Suffice it to say that beginning in 1983, the Islamists expanded their murky network in the subsequent six years and seized power in 1989 through a coup. Once they usurped power, they began to derail the nation-building process. This in turn triggered uunprecedented protests throughout the country – in the south, west, and east. The eventual legacy of the NCP/NIF regime was the eventual fragmentation of the Sudan; the most significant of which was the issue of South Sudan.

Symptoms of fragmentation were also manifested in the Blue Nile, Kurdufan and Darfur areas. Indeed, instead of bolstering nation building, the next 30 years saw a phenomenon of disintegration and fragmentation in the country. More ominously, the Sudan became a hub for terrorism during this period.

The purported aim was to change the world using their version of Political Islam; not the real Islam. Bin Laden set camp in eastern Sudan and he was there until 1996. Thus, instead of working for domestic reconstruction, the Sudan became embroiled in elusive regional and global agendas of fomenting chaos.

The biggest mistake in Sudanese history was the secession of South Sudan. South Sudan should not have separated – by any argument. The liberation movement of South Sudan was about the right to self-determination. Indeed, whether it is John Garang or any of the leaders of the time, their choce was 99% in favor of unity. The desire to separate was perhaps 1%. So why did secession happen? Was it because the North wanted it? Was it influenced by others? In retrospect, a lot of analysis can be made regarding this matter.

Internal developments were pushed and goaded. But they were pushed and relegated to ultimately opt for secession in 2011. At the same time, the protests in the West and East did not subside. The situation in the South itself was not over. There are still unresolved issues such as Abyei and others. Disputes on whether there should, or should not be, oil allocation remain. Similarly, the Darfur problem continues; same with Kurdufan and the Blue Nile – none of these have been resolved until yesterday.

The Sudan, with all its resources, is considered as the breadbasket of the region. The country’s current situation, however, shows otherwise; its economy has been embezzled; it is drowning in debt; and the economic difficulties of its population have worsened. The past thirty years have thus halted the relative progress in nation-building of the preceding period to entail fragmentation of the country.

The worsening economic and security situation and the deterioration in livelihood caused bitterness amongst the population. This resulted in spontaneous and powerful revolts. This eventually led to the overthrow of the regime in 2019. The popular revolts were not led or directed by any particular entity. But although the people may not have articulated their wishes through a written manifesto, the message was clear and unequivocal: “we have had enough”.

When the regime was overthrown by a popular uprising in 2019, the country stood at a crossroads. It needed to move away from the 30-years-long NCP regime to a new rule. The path was clear: move away from the fallen regime towards a transitional stage and then from a transitional stage towards a gate of safety (or a new and healthy political dispensation). This is the shortest and easiest route. To enter the gate of safety, it would have been necessary to install a new system of government by gleaning key lessons from the accumulated experience. In turn, the new system of government, acceptable to the Sudanese people, would have enabled the country to cross the gate towards safety. Unfortunately, the path deviated and was derailed from this route.

The post-2019 period was littered with what I refer to as “distortions”. Different groups began to claim the revolution as exclusively their own; to claim to have brought about radical change for the people and country on their own. A spontaneous popular revolt, which happened in response to dire internal developments after years of unresolved grievances and patience, was now being claimed as the project of one group or another. Some began to claim “I’m the revolution”, “we did this”. Different groups began to sprout from all corners. The country had never witnessed such confusion. The question remained; how can you claim to have brought about the change that the population itself brought about spontaneously? And if you are going to say that you have contributed in any way, now is not the time.

Similarly, if you are going to contest power, now is not the time. Once you have crossed the critical stage where you have secured stability, then you can talk about, or envisage, competition for power. This is a transitional period and there is no reason to contest power during this period. It is also not the time to divide people along military and civilian lines. This is a transitional stage brought about by a popular uprising. Its roadmap is clear. The key goal at this time is to design the bridge that can take you across to the gate leading towards safety. How do you get there should be the leading question?

For the Sudan to reach the gates of safety, a new situation must be in place. This new situation will be crystallized in a new system of government which must be chosen and elected by the people. This is the debate that began during the first month of the first year. The distorion of the main process or direction had led to a wrong outcome or inclusion in the case of South Sudan and associated instability.

As stressed earier, it is counterproductive to fight over ownership of the revolution at this point in time. This is not the time for settling scores or squabling about power. This is a transitional phase and these divisive trends must not be contemplated. They may arise once the destination is reached.

The war between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) is a legacy of the NCP’s attempt to build its own army and create security institutions in its own image over the past 30 years. What does the Sudanese army really look like? What do the country’s security institutions look like? How were they established? Much can be said about all of these. What is the difference between the RSF and the SAF? Both belonged to the same regime – they were created from it. One can raise a number of issues regarding the structure of the former Sudanese Armed Force; both in respect to political and ideological tendencies. But this is not the time to do so. Furthermore, there are armed groups in Darfur, Kurdufan, Blue Nile and the East that have not been incorporated into the process. In the event, the building of a national, sovereign defense institution has its own process whose crystallization will require a long time. There is no reason to presume that it has a direct linkage with the transition process in question and that it must be resolved first.

One of the disruptions raised in recent times was the issue of integration of the army. The demand was for the RSF to integrate its forces with the army. This should not be controverisal in principle. The question of a unitary army is not controversial or a matter that must be glossed over. But it does not have to be implemented in haste now, tomorrow or after tomorrow. Implementation must be carried out through meticulous preparations. For purposes of emphasis and clarity, it must be underlined that in priciple and as a Sovereign State, Sudan must have a unitary defense institution.

How this is built is another process that should not be conflated with what we call the transitional phase. Raising this matter will only be seen as a pretext or distraction. Indeed, it cannot be established prior to the formation of a civilian government. The formation of a civilian government is in fact a significant topic in and by itself. One has to reach a satisfactory answer on this topic first. To say that military unification must occur prior to the establishment of a civilian government may be tantamount to putiting the cart before the horse. Where will this then lead?

How does the issue of military integration morph into a cause for conflict? And what is the actual reason for conflict? What does a power struggle between two individuals mean in this context? As we have seen over the past 30 years, when substantive issues are mishandled, they result in meaningless conflicts and complications. This is inexcusable. As I mentioned earlier, there is no force other than the army as a whole (as an impartial force) that can shoulder the burden of the transition process towards the gates of safety. That is why we as neighbors, as partners, maintained our direct relationship and all our consultations with Burhan. Not because this is his own personal issue, but because, at this particular stage, the national army is the body that can move the country towards the gates of safety; because it is an impartial force; and because it is deemed as capable of guaranteeing the safety and stability of the country.

Why did this war break out? What is the reason for the conflict? Is it a conflict between civilians and the military? Is it a conflict within the army? Where did the conflict originate to cause such destruction? With what arguments can you justify any of it?

At any rate, it must be reiterated that the transitional phase must remain in the hands of the army. It cannot be replaced. Anyone watching from the outside, as we are watching the developments closely as neighbors, cannot inject arbitrary parameters or qualifications of capacity and/or age for preference of one against the other. The crucial thing is that the army must shoulder the burden of the transitional stage and steer the process to reach the gates of safety. It must then hand-over power to the Sudanese population who will subsequently establish its own insitutions of governance.

To dwell on the consequences of the war will only compound and eclipse the quest for a lasting solution. One must understand the conflict’s historical genesis and the sequence of events that led to it. The media tends to focus and exaggerate the consequences. This will only add fuel to the fire.

The approach must be reversed. War must stop – without any debate or equivocation. The actual causes that led to the conflict must be properly identified to prevent any recurrence of such a tragic situation in the future. In a nutshell, the underlying problem must be resolved. And all of us have to work on this.

Sudan’s neighbours are the countries that are most affected by the unfolding events. It is accordingly imperative for the countries of the region to work in partership and to hold consulations on the resolution of these problems as was indeed the case in the past with the problem of South Sudan. But most importantly, the central role will invariably be played by the Sudanese people. This must be accepted as an operational principle. Within this framework, the most urgent task at this point in time is to bring an immediate end to the war. After ensuring a permanent end to the war, all the complications that triggered the confict must be addressed and removed. The transitional phase must subsequently be allowed to progress unhindered and move the country towards the gates of safety.

Question: For obvious historical and geographical reasons, Eritrea is one of the neighboring countries that is closely and directly affected by the situation in Sudan. In addition to bolstering warm bilateral ties, Eritrea has been playing a modest role, in a discreet manner,in the promotion of the objectives of the transitional phase and beyond, especially in view of its good ties with all Sudanese political forces. Eritrea’s role stems from its conviction on the neutrality of the Armed forces and the need for a participatorytransiitonal political phase. In this respect, what is Eritrea’s stanceand outlook on a lasting solution to the conflict and, more generally, on the peaceful political peace process in the Sudan?

What I have discussed so far, in very broad terms, can be viewed assetting the historical context and the backdrop to the current events. As far as we are concerned, our commitment to the Sudanese cause is not anchored on a random whim or mood. Eritrea’s profound relations with the Sudan does not require anovel explanation because the memories are still fresh from our recent history.The extent to which developments in the Sudan over the past 30 years affected us is a well-known fact. So, our engagement with the cause of the Sudanese people is not optional or a matter of choice.Stability, peace and development in the Sudan are shared and common interests for both of our peoples. As such, there is no reason why we should not contribute to the extent that we can in this endeavour. This does not detract from the fact that the issue of the Sudan is first and foremost the responsibility of the Sudanese people.

In general, the stability of other countries in our neighbourhood is not optional and a matter of choice. Regional stability is vital because it reinforces domestic stability; makes it reliable and ensures sustainability. One cannot walk away from it. As such, when the popular uprising happened in 2019, our engagement became stronger as required by the circumstances. We did not choose to remain on the sidelines and “pass the buck” to others. We carefully analyzed the evolving situation and assessed the prospects of acting positively? How can we demonstrate our friendship to the people of the Sudan in their hour of difficulty?

Taking stock of all of the turbulent winds, no one could afford to ignore the potential consequences of the preoccupyingdevelopments in the Sudan with its ramifications both inside the country but also in the region as a whole. The news that was being churned out was unsettling… “Nubians have been killed in eastern Sudan”, “killings took placein the Blue Nile region”, “villages have been set on fire in Darfur,” etc. This cannot but engender concern in the neighbourhood.

After 30 years of oppression, the betrayal of the Sudanese people has given rise to this current point. The country has embarked on a transitional phasetowards a better future.

For us, the modest role that we can play must be predicated on a clear strategy of engagement. The primary concern was some discernible negative trends that could derail the process. These emanated mostly from opportunistic movements that seemed bent on sowing discord within the transition process.

As it will be recalled, the Sudanese army chose to stand by the people during the popular uprising in 2019. It refused orders to “arrest” and “kill”. It chose to stand bythepeopleas it knew their aspirations and wishes. Also because it is a product of the people. The role it played in those crucial times cannot be underrated. For this reason, it possessed all the credentials to shoulder the burden of transition. These considerations prompted us to initiate our engagement and maintain continous consultations with the Sovereign Council. Obviously, they know their case better. Nonetheless, we maintained constant discussionsand shared our views in order to contribute what we can. In this spirit, we also put forward our proposal which cannot be fully discussed here for paucity of time. As I stated earlier, the historical contexts and trajectories are taken into account to draw appropriate lessons from the past.

Nation-building processinvariably encompasses different aspects – of peoples, of citizenship, of opportunities. Even if we look at the experiences of others, the reference points are clear. The trajectory involves a transitional phase to catalyse a cogent climate for a new, viable,7 and sustainalepolitical dispensation that allows and guarantees the Sudanese people to ultimately make their choice. With this in mind, our proposal clarifies the strategic vision, from our perspective, for the transitional phase and beyond.

Obviously, there may be several initiatives from different quarters. For our part, we are not really interested in competing in a bazaar. We will not be prompted to start an initiative in a competitive spirit. Our focus is on what we can really contribute; without publicity and in a very discreet mode. We have been working along these lines for the past four years. This is squarely based on partnership, understanding, and mutual respect; not our presumptouspreferences. And of course, it is based on listening to the opinion of others.

It is always counterproductive to try and “analyze” and “solve” issues after they have flared up. For this reason, we have been in constant communication, before the conflict erupted, with the stakeholders and providing our views and suggestions in a timely manner. In this context, we explained that the merging of the forces and the establishment of a sovereign army in Sudan is not a controversial topic in and of itself. But itsimplementation has its own dynamics or process. Obviously, the doctrine, configuration, capabilities, composition, size, and other fundamental military parameters are also part and parcel of the institutional building of a unitary army,

Unfortunately, the journey of the past 30 years has completely hampered this process. In addition to this, as mentioned earlier, armed forces were established that are outside the arena of the national army. Taking all of these factors into account, it is counterproductive to place the issue of the merging of all forces and the building of a unified army as aprecondition. This would only hinder the political transition process. In this spirit, we had indeed made our opinion clear; that this issue should not be used as an excuse to trigger any conflict.

We did not publicize it, but we had made our position clear to all the stakeholders. We persisted in our consistent engagement and exerted all necessary efforts to avert the eruption of any potential conflict. Still, we will continue to engage to bring restoration to the process that has been derailed. Our engagement cannot be erratic that is interrupted or abandoned when the conditions are not conducive. It is an obligation – not a choice.

Indeed, as far as we are concerned, the Sudan is unlike any other neighbour. Our relationship bears unique historical characteristics. As such, whether for the short-term or for the future, we are committed to a judicious engagement, and this goal is not something we can postpone.

What is disconcerting is the trend that we see and that may further exacerbate the situation. The war must stop. Disinformation that aggravates the situation must also cease.

(Source: Shabait)