By Dr. YONAS WORKINEH

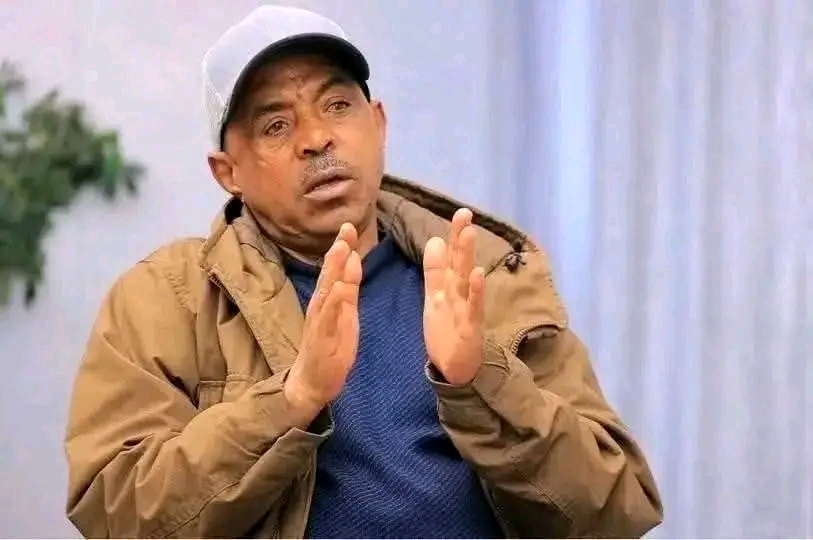

Jawar Mohammed is a highly influential figure in Ethiopian politics, recognized for his role in organizing and leading protests in Oromia over the years, both behind the scenes and on the front lines.

He is renowned for his commitment to peaceful resistance, spearheading popular demonstrations against Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s government.

After Abiy assumed power, Jawar returned to Ethiopia and became a vocal critic of the administration.

Jawar faced charges related to the killing of a police officer during unrest sparked by the murder of singer Hachalu Hundesa, leading to his imprisonment for over a year and a half.

As the leader of the Oromo Federalist Congress Party, Jawar published his book, I Will Not Regret, in Nairobi, Kenya, on December 10, 2017. The book narrates his political journey and life experiences.

On December 19/2024, In an interview with BBC Amharic, Jawar discussed pressing national issues, his potential future role in Ethiopian politics, and the current state of the country.

BBC – Prime Minister Abiy came to power with many positive words and actions. However, the Tigray war broke out soon after; conflicts continue in Oromia and Amhara regions. Hunger, displacement, and the high cost of living in cities have become a feature of the country. In your opinion, where is Ethiopia heading in this?

Jawar : – Abiy was not on the line from the beginning. . . . [At the beginning] We were going to fight with the TPLF; they would leave power; they would leave central power, after we reached an agreement, who would be after they left power? I spoke to him when Abiy’s name came up. It was clear to me then.

Ethiopia had to transition from the EPRDF’s one-party rule to a multi-party, democratic system; it was the only option that would not lead to conflict.

Even before he took power, and before his name was known, it was clear to me in my conversations with him that he had no desire to build a democratic system. It was clear to me that he dreamed of transferring a dictatorship from one party to one individual. That is why I opposed him.

But at that time, what people saw was that the feeling of change was so strong that only the TPLF should be destroyed, but no one should come, so I couldn’t convince people. First I couldn’t convince the OPDOs, then the people. That’s why I stopped, but it was very clear to me.

After that, I saw what was happening in the first year. When it came to discussing and leading this transition, I said, “I will lead you through it; we don’t need a common roadmap,” the response was heard. While the good was visible, the path to democracy itself was already being paved. In the end, when the election was held, when the forces that were considered to be competitors were attacked, the person woke up, but from the beginning, Abiy never had the desire to transition Ethiopia to democracy.

BBC: Fighting continues in the Amhara and Oromia regions of the country; the Pretoria Agreement to permanently end the conflict in the Tigray region has not been fully implemented. . . . Do you still believe that there is a chance to return to democracy, to bring the country back on track?

Jawar: There is a chance. But I don’t think Abiy can return to the right path with his current attitude and arrogance. Because he doesn’t understand Ethiopia. He doesn’t understand not only Ethiopia but also a multi-ethnic country, the current world situation and the current situation in which Ethiopia is. He doesn’t have the desire to understand. An island of prosperity has been created in Ethiopia. A place where only Abiy and those around him roam, completely ignoring other people, and not understanding the way of life of other people.

I recently went to [Addis Ababa] and wrote something on Facebook. It said, ‘The people are tired, they are tired.’ It was true. I went around and saw the people. I used to go around the city day and night and see the people. Then I met the ministers one by one.

When you talk about the economy, they say, ‘The economy has never grown like this.’ . . They pretend that honey and milk flow through pipes in every home.

When you talk about war, Amhara region. . They are divided; they are disappearing. Oromia region has no problem. Tigray is their own issue. . . They believe [the Prime Minister]. . . . They believe their own lies. We cannot get back on track with their views. But will we just watch? We will not just watch. Our country is our people. It is where we have grown; it is where we have spent our lives. We are not going to let them take us down. Not only themselves, but they are going to take the country down. Can we bring Ethiopia and its people back on track? Yes, we can. But if we expect them to bring us back, they are taking us to a worse place than the misery they have put the country in over the past six years.

BBC: People who knew Jawar before his arrest saw him as a vocal critic of the government and active in politics. But after his arrest, we saw Jawar as a leader in the center. What change did prison bring to you?

Jawar: The biggest thing is not that I was the only one in prison during my imprisonment. As I said before, the Ethiopia I left behind and the Ethiopia I found after I got out of prison were different.

Before I went to prison, the clouds of trouble, the clouds of war were gathering. When I came out of prison, fires were burning everywhere. So, as a person with a voice and influence, what can I do to save the country and the people? I thought. If I came out and went back to activism and criticism, it seemed like adding more gasoline to the fire. So I decided to let go of that and focus on using my voice, my connections, my interactions, advising, disciplining, and working to mobilize the diplomatic community. After I got out of prison, when I went to the diaspora and spoke to the people about peace, I was met with great resistance. Only I could do that.

I had political capital associated with the struggle. I was doing that by going abroad and using that political capital, and because the people at the time were very divided by supporting the armies of different sides, I was doing that in order to reduce the war market and expand the peace market, and to pressure both the government and the rebels in the forest to come to peace.

I did my best to talk to the people about peace, then to the diplomats, then to the country’s authorities and the rebel leaders. I tried a lot. But what I saw was that there was no commitment or interest in bringing the country to a general peace, a radical peaceful change, but to buy time. In fact, I saw that things were going back to the way they were. If this continues, it will only get worse; keeping quiet and advising, persuading, begging, it won’t do much. . . . I think it’s pointless to continue there.

BBC: So you’ve returned to your previous active political involvement?

Jawar: It is impossible to go back to the past. We can only move forward.

BBC: I bring this up because the next election is not far away. You are also a member and leader of OFCO; what role will you play in Ethiopian politics going forward?

Jawar- I will have an active role. I have just started talking and writing about these children [people of prosperity] who have entered into a very dangerous situation. Total ignorance and arrogance.

BBC- You mean the people of prosperity?

Jawar- The people of prosperity, Abiy and the people around him, are in total ignorance and arrogance. This is what they have entered into.

And hunger has blinded their ears and minds. This is a danger for them and for the country. So what I want is for us to talk. We need to talk.

Especially now, what do you think they are doing? They used the Amhara political ‘camp’ when they attacked us and Tigray. Now, when they clash with Amhara, they are hiding in Oromo; they want to attack Amhara in the name of Oromo, while confronting Oromo.

This is putting Ethiopia in grave danger. The Oromo people do not want this. The Oromo people fought against oppression by the ruling classes that came from the Amhara yesterday. They also fought against oppression by those who came from Tigray. But they fought not for a dictator to come to power and beat Tigray in his name, not for the Amhara.

We are to resolve our political differences with the Amhara, the Gara, and the Somali through dialogue and debate, and establish an Ethiopia that is for us and for all.

It is to establish a just, democratic federal Ethiopia. But now, if people like me who have a voice remain silent, I have seen the threat of using the Oromo sentiment to exploit their war with the Amhara, so I went there [working] with the belief that this must fail.

BBC: So you will participate in the next election?

Jawar: Elections are a luxury in Ethiopia now. There is a saying. If there is a head, you can tie a turban. But if there is no head, what will you tie it to? Elections can only be held when there is a place controlled by the government.

Today, the government in the Amhara region controls only Bahir Dar and a few other areas. In the Oromia region, apart from some major cities, there is another hotbed of insurgency. How many of Ethiopia’s 547 parliamentary seats can be used for elections? If at least 2/3 of the 547 parliamentary seats in Ethiopia are not used for elections, then the elections will not be valid.

So, in the current situation, it is pointless to talk about elections. First, we need to be able to return our country to peace. If relative peace comes, we can talk about elections. If relative peace comes and the opportunity for elections arises, I will be in the first row.

Five years ago, we were the ones talking about elections. We had a country. We had a system. But in the current situation, talking about elections is distracting the people. The priority should be to put pressure on the government in Ethiopia, because it is the government that is the main obstacle to peace negotiations and talks.

BBC – The government is often heard saying that it is ready for peace negotiations and dialogue with the militants. There have been occasions when the militants have also said that they are ready for peace. But the expected peace has not yet come. What do you think is the reason for this?

Jawar: The government wants peace for the sake of peace. To bring this rebel with money and other things. There was no rebel in Oromia and Amhara regions or Tigray region five or six years ago. What led to the rebellion? Before the rebels came in Gondar and Welega, Addis Ababa and Finfinne were already in the thick of it.

Political disagreement, lack of interest in resolving existing political differences around the table and Abiy’s decision to establish a personal dictatorship by closing the political space. It is the differences that need to be resolved in the heart of the country’s capital that are the reason for entering the jungle.

What we are talking about is a comprehensive peace, a comprehensive political settlement; the political differences that have brought us to war must be resolved through negotiations and dialogue around the table. They do not want this. They want to send the priest Sheikh, and the businessman, and send him money. Some soldiers will come. We have tried, and we have brought more than half of the ONLF army with us, along with the Aba Gedas. Since the political space has continued to shrink and they are unwilling to resolve the main issue that caused the conflict, they have since expanded and today they are operating more than the government’s army in the Amhara and Oromia regions.

So, what we are talking about is not a peace of the tongue, but a peace that brings fundamental political differences from the jungle to the table, from the mouths of guns to the table.

BBC- Since you raised the issue of militants, it is appropriate to ask this question here. The issues raised by militants are not far removed from the issues you raised about Oromia during your protest. Have those issues you raised then been answered or have they been pushed aside?

Jawar – They are confused. Not only confused, but they have become worse than those questions. The questions that were raised then, such as equality, language, and urban issues, are not being asked today in Ethiopia. Today, the question has become existential. The people could not enter the land of Keye. While training thousands of militias, the militia has no salary, it robs people. Those who have forests rob people. Those who are sent to maintain order on behalf of the government kill people. It robs people. Today, the Ethiopian people, especially in the Amhara and Oromia regions, are not raising the questions that you say we used to raise.

It is a fundamental question of entry and exit. Many of the young people who joined the Oromo Liberation Army leaders Driba Kumsa and Jal Mero in Oromia, and Eskinder Nega and others in Amhara, did not do so because they did not articulate their political demands. First, the closure of the political space deprived them of freedom. Second, the kidnapping, killing, and persecution that occurred when they entered their villages prevented them from living. They had to enter to save their personal lives and advance their political demands. . . . Therefore, the political demand was obscured and the existential demand covered the political demand; it meant that it was suppressed.

BBC: When you look at the current situation in Ethiopia, what worries you the most? What keeps you awake at night?

Jawar: The destruction of the country. Because when we were fighting, there was a government. We were pushing and shoving the government, asking for the repression to be reduced, for the rights of citizens and groups to be given. Because it was the trunk. Now the trunk is rotting and dying.

The danger of the country collapsing is at a very dangerous level. . . . People who say Ethiopia will not collapse are collapsing it every day. If the country collapses, I think maybe I am getting old and the country collapse worries me.

As I often say in my book, when I developed the strategy for the Kiron movement from 2007 to 2012, I was thinking of a system-wide upheaval, a ‘regime change’.

Meanwhile, the children who were studying with me, and whom I was teaching, started the ‘Arab Spring’ [Arab uprisings]. What was the thinking before that? You overthrow a dictatorial system through popular uprisings and build a democratic system. We did not see a third option. State collapse [disintegration of the country]. Looking back at the collapse of Libya, the collapse of Yemen, the collapse of Syria, if we collapse the EPRDF, it could be the collapse of the country. So we put pressure on the forces within the EPRDF that want a moderate change to come to power. The fear that I had at that time was mistaken for a ‘state’, and now I see it again. And now I wake up thinking that once a state collapses, you can fix a dictatorial government; you can fix a state whose economy is ruined by removing its leader. It is very difficult to rebuild a country once it collapses. . . . Once a country like Ethiopia, which is complex and has the interests of many foreign powers, is divided… But when it comes to the dissolution of a country, one must be careful. If Ethiopia is dissolved, Oromia will be left, Amhara will be left, Tigray will be left. If the Ethiopian state is dissolved, it will be divided…. It will be like a piece of paper dropped from a roof.

BBC- The government has now established a National Reconciliation and Consultation Commission to address the issues you raised and to discuss other issues. Of course, they have not yet completed the agenda. More than 10 opposition political parties have also submitted their objections and announced that they will not participate. Among them is the OFC, of which you are the leader. But I want you, as Jawar, to answer this. Do you believe that the consultation commission will bring about the desired change?

Jawar- When the change came, we proposed three issues. One is the national dialogue. We considered the issues of national reconciliation and identity and border issues as issues that would emerge from that. Part of our transition plan. They left the national dialogue and temporarily established the National Reconciliation and Identity and Border Commission, which was dissolved after three years. ‘National Dialogue’ is held in a country for two reasons. One is to prevent war. When political differences are very strong, to reduce that tension and prevent it from leading to war

It can be a way to prevent a pre-war war. Another way is to hold a post-war ‘national dialogue’ after a war, where the political issues that led to the war do not lead to another war, and to heal the wounds and wrongs committed during the war.

When the Ethiopian National Dialogue began, it was founded in the midst of a war: the war was going on in Tigray. It was also going on in Oromia. I asked while I was in prison. After I was released, the people who were elected to the ‘National Dialogue’ came and asked me. What was my proposal? The idea is very good.

We should have done it six years ago, in 2018. Better late than never. The starting point for a national dialogue is crucial. The political elites who decide to discuss, the political organizations that will discuss, should have their input and agree on the discussion law. So don’t rush it, don’t rush it.

He is one. Secondly, as I said before, the ‘National Dialogue’ [National Consultation] can only be effective after the war is over. So, they say that they will work to stop the war, the Tigray war, the Oromia war, and that those who are fighting should come to the stage, and we will not support it. They continued without doing that. It means that the war in the Amhara region has been added. Today, the ‘National Dialogue’ cannot be held in Ethiopia; it means that Abiy is talking while looking into a mirror.

BBC: So you have doubts about its effectiveness?

Jawar : -The issue that has been resolved is Oko. As Professor Merera says, it is ‘dead on arrival’. Since it was a broken thing from the start, what will happen in the current situation is that the system should be presidential and it cannot have any effect other than making Abiy president.

BBC – If everything you think is right, do you have any desire to lead Ethiopia as Prime Minister?

Jawar: As I told you before. ‘Mataa jirutti sabbata marani’ is the one who wears a turban on his head. For me, the most important thing is that we have a country.

We are entering a stage where we say we do not have a country. . . . Let the country return and the Prime Ministership is not a problem for farmers. What is the one thing that has created the problem? It is dangerous to become Prime Minister, to become a minister without preparing yourself for what knowledge, maturity, and wisdom are needed to lead a country, without understanding the complexity of the country and the complexity of the world. So, who should be Prime Minister for me? This is the second stage.

I am not saying that we should rebel now. I am saying that we should talk. The country is in great danger. Our economy is in a state of collapse. The people of Ethiopia have always been poor, but at this level, the people have never been in difficulty. . . . What is the result of this? One is the result of the war: the money left over from the war was spent on luxury resorts and palaces.

The Creator has… Why does Ethiopia need a new palace? Is the problem of the Ethiopian people a resort?

The problem of the Ethiopian people is the lack of adequate and affordable land. The problem of the Ethiopian people is the lack of peace where farmers can farm safely.

The problem of the Ethiopian people is the widespread lack of road transport. . . . So what should be prioritized in Ethiopia? There is a priority imbalance in Ethiopia; it is imperative for Ethiopia to correct that.

BBC: Given the tensions and political strife in the Horn of Africa, do you feel that Ethiopia is losing its previous voice and role as a mediator?

Jawar: It has lost a lot. Ethiopia used to be a country that provided security to other countries. It did so not only because it had a strong army. It was also because it was stable at home. The internal war has greatly weakened the country’s capacity. It has become a source of unrest, not peace, to its neighbors. We have become unnecessarily involved in conflicts with our neighbors. There is no national vision, no national project. . . . We have a special relationship with Eritrea and Somalia. Our social and economic ties with the two countries are incomparable. It is very complicated. Ethiopia is in the middle of the two countries. Our role should have been to repair and restore the historical ties we had with these countries and strengthen our economic and social ties.

. . . There are sensitive historical circumstances with Somalia. Our relationship was good in the first five years of Abiy. We strengthened our relationship with Somalia. But we did not establish the economic, political, and security relationship that we should have, beyond stabilization. We did not discuss it; it was not written. . . . So it went from being national to being personal.

Ethiopia needs a seaport. Yes! We need a navy not only for trade but also for the region. The existence of an Ethiopian navy is important not only for Ethiopia but also for the region. Ethiopia is a country with a large population, a large army, a large land area and a large economy. Both the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea have become vulnerable to various powers coming from far away. Many powers are coming. Somalia cannot protect the interests of this region on its own. Neither can Eritrea.

If they cooperate with Ethiopia, it is possible to reach an agreement based on mutual interest, not on the pretense that Ethiopia will be the best, but on a regional connection that can be for Somalia, Eritrea and Djibouti. . . . Instead, we are in danger of going through the same pretense that we have been tired of before. . . . Suddenly, it was said that we have agreed with Somaliland. We have agreed just to agree. To fool the people by saying that Ethiopia has found a port. And the people are sensitive. They want a port. They have ‘misused’ that desire of the people. They humiliated them. Even after they entered, instead of negotiating and finding another way, we got into what was seen. In the world, China and America, the East and the West, agreed with us. They thought of us as a troublesome country. . . . We are being seen as the cause of trouble in the region.

None of the countries in the region have a healthy relationship with the current government in Addis Ababa. . . . As I move around here and actively follow the situation, I feel pain. As a citizen, when you hear what is being said about our country and our leadership, I feel pain. I want to be proud of my country. I want to be proud of my leaders.

Ethiopia needs a capable leader. The power that claims to lead Ethiopia must provide a capable leader for that country and its people. But if it cannot, it must be able to say it cannot, and it is very sad to humiliate the country and itself to this level.

BBC: You currently live in Kenya. Do you have any security concerns living in Ethiopia?

Jawar- It’s not just for fear. First, it’s better for my job here. Second, after I got out of prison, when he went to Erecha, they arrested all my guards.

Then, when we discussed it with many people, including party members, my position at the time was that no matter what, there should be no problem with the current fire because of me.

So these people are trying to make things worse by trying to get me to leave, so I came to Nairobi, thinking, “What’s the best?” But I don’t live here all the time. I work in Europe. I travel around Europe a lot. But Nairobi is a beautiful place. Don’t be jealous!.